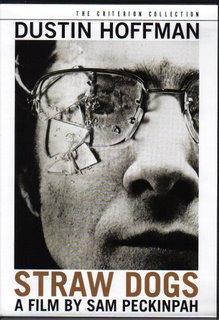

In the wake of the recently released Sam Peckinpah DVD boxed set, I’ve been prepping myself by watching some of his earlier released discs before I plunge headfirst into the goldmine. That’s not to say that some of Peckinpah’s masterpieces haven’t already been unleashed upon the public. Far from it. The infamous director arguably has a stable full of classic films in his short if uneven oeuvre, including this staggeringly brutal meditation on violence starring Dustin Hoffman. Straw Dogs, based on a novel by Gordon Williams entitled The Siege of Trencher’s Farm, was notorious when it originally hit theater screens in 1971 (the same year that Eastwood appeared as the titular Dirty Harry and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange pillaged patrons with its dystopian SF parable) and its unbridled power and relentless capacity to provoke and outrage viewers hasn’t abated one bit. I’ve seen it a few times before and its lucid yet bewildering treatise on the violence that swims within even the most “civilized” of individuals still continues to fascinate as well as sicken and horrify me. Although Peckinpah had previously dealt with the theme of man’s predilection toward committing carnage, and the almost ritualistic need to do so, most notably in his sure-fire masterpiece The Wild Bunch (newly re-released with the boxed set), Straw Dogs is probably the most brilliant and methodical examination of what motivates a person to kill that the director ever created. The film’s main question is simple: What will it take for a “civilized” person to destroy another person? But it’s the can of worms that ensues that is even more troubling. In killing someone, what do you surrender within yourself? And is violence the natural state of man? The answers to those conundrums are not proffered in the course of the film’s running time, though if they had been, I’m not so sure we would be too pleased. It’s potent stuff, to say the least, but also greatly entertaining.

In the wake of the recently released Sam Peckinpah DVD boxed set, I’ve been prepping myself by watching some of his earlier released discs before I plunge headfirst into the goldmine. That’s not to say that some of Peckinpah’s masterpieces haven’t already been unleashed upon the public. Far from it. The infamous director arguably has a stable full of classic films in his short if uneven oeuvre, including this staggeringly brutal meditation on violence starring Dustin Hoffman. Straw Dogs, based on a novel by Gordon Williams entitled The Siege of Trencher’s Farm, was notorious when it originally hit theater screens in 1971 (the same year that Eastwood appeared as the titular Dirty Harry and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange pillaged patrons with its dystopian SF parable) and its unbridled power and relentless capacity to provoke and outrage viewers hasn’t abated one bit. I’ve seen it a few times before and its lucid yet bewildering treatise on the violence that swims within even the most “civilized” of individuals still continues to fascinate as well as sicken and horrify me. Although Peckinpah had previously dealt with the theme of man’s predilection toward committing carnage, and the almost ritualistic need to do so, most notably in his sure-fire masterpiece The Wild Bunch (newly re-released with the boxed set), Straw Dogs is probably the most brilliant and methodical examination of what motivates a person to kill that the director ever created. The film’s main question is simple: What will it take for a “civilized” person to destroy another person? But it’s the can of worms that ensues that is even more troubling. In killing someone, what do you surrender within yourself? And is violence the natural state of man? The answers to those conundrums are not proffered in the course of the film’s running time, though if they had been, I’m not so sure we would be too pleased. It’s potent stuff, to say the least, but also greatly entertaining.Set in the west coast of England, in a quant if dismal little village in Cornwall, American mathematician David Sumner (Hoffman) and his wife Amy (Susan George), who is originally from the village, move into her late father’s ancestral stone cottage with dreams of starting a new life away from the crime and pollution of the States. Of course, this being a Peckinpah film, David’s and Amy’s attempt at domestic bliss is shattered by a horrendous incident and David is forced into finally making a stand against his provokers, as well as coming to grips with the darkness within. The screenplay by David Zelag Goodman and Peckinpah deftly thwarts our expectations at every turn by constantly twisting or changing the plot points leading to the inevitable. The road to perdition may be unavoidable for David, but there’s no clear journey there and the catalysts that we were so positive would ensnare him or push him over the brink wind up being meaningless in the big picture.

Peckinpah’s films (at least the important ones) are like cinematic Rorschach blots, never quite revealing the same thing to everyone. To some, the director is a macho provocateur wallowing in misogynistic representations of women and celebrating the most vile, ugly, and brutish characteristics in men. To others, he’s the last great American director in the tradition of Hawks and Ford before the film school brats (e.g. Coppola, De Palma, Lucas, Scorsese, and Spielberg) usurped the throne of 1970s Hollywood, a maverick larger-than-life personality who challenged the celluloid dream factory and lost. I guess I’m somewhere in the middle of the two camps. There’s no doubt in my mind that Peckinpah’s best films (Ride the High Country, Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia) are the work of a mature and gifted artist, though many of them (Straw Dogs, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia most notably) also betray a profound misanthropy that borders on the morbid and nihilistic. The characters in the latter two films both transform into their new roles as men of violence so thoroughly that it borders on the psychopathic, though Warren Oates’ Bennie, from Bring Me the Head, at least hasn’t forsaken redemption altogether. He at least still covets the idea of redemption, even though his instincts know better. When David Sumner crosses over in Straw Dogs, there’s not even the slightest glimmer of reason left in him. He fully accepts his new role as killer angel, and as the protector of his bloodied homestead without a trace of self-knowledge or insight. He’s pure animal instinct at that point, and the transformation/rampage against the attackers is horrifyingly funny because of his lack of self-control. There’s also nothing more disturbing than witnessing someone lost within the thickets of his own personal moral oblivion.

Every time I return to the film, I’m reminded just how coherent and troubling its “message” is. I’m also stunned by how thorough Peckinpah’s lust to hurt us truly is. Obviously, he wants to shock us with the overt build-up of tension and the orgasmic violence that eventually overcomes us. But he more importantly wants to incite a riot of thought inside us, as well. Forget David Sumner. What would you do in the same situation? And would you like it?

Straw Dogs has been released onto DVD a few times here in the States, though never better than in the 2-disc Criterion Collection edition (which is now sadly out of print). The print is superb—the best I’ve ever seen it—and the wealth of extras (including two excellent essays, a feature-length documentary on Peckinpah, and some candid interviews with actress Susan George and producer Daniel Melnick) really help to clarify some of the film’s trickier and more unsettling motivations. Though really, I’m not sure any justification or explanation can tame this dark beast of a film, even thirty-some-years on.

No comments:

Post a Comment